Perched in the high Andes just outside of Cusco, Tambomachay stands as a quietly impressive testament to the practical genius and spiritual worldview of the Incas. This archaeological site brings together refined stonework, a sophisticated hydraulic system, and enduring ritual meanings rooted in the Andean relationship with water, landscape, and power.

The Context of Tambomachay: Location and Surroundings

Tambomachay is located approximately 8 kilometers northeast of central Cusco, at an altitude nearing 3,700 meters above sea level. The site rests alongside one of the ancient roads leading towards the Antisuyo, which was one of the four main regions (or suyos) that radiated from the Inca capital. Today, visitors will find it adjacent to the paved road that winds from Cusco toward Pisac and the Sacred Valley, making it part of a circuit that includes other sites such as Puca Pucara, Qenqo, and Sacsayhuaman.

The area around Tambomachay is characterized by rugged limestone outcrops, native ichu grasslands, and seasonal streams. Local residents from nearby communities such as Ccorao and Ccorcca often pass by on foot or bicycle. While tourism is a significant activity today, many people still use these highlands for grazing livestock or collecting medicinal plants. The proximity to Puca Pucara—a reddish fortification whose name means “Red Fortress” in Quechua—has led some historians to note that this corridor once had both ceremonial and strategic functions. The relatively short distance from Cusco meant Tambomachay could be visited by members of Inca nobility as part of ritual circuits along the ceques (sacred lines connecting huacas or holy sites).

Etymology and Interpretations of "Tambomachay"

The name Tambomachay is generally understood as a compound of two Quechua words: “tampu” (or tambo), meaning lodge or roadside inn, and “mach’ay”, which can signify cave or a sacred hiding place. Combined, it is often rendered as “the resting place of caves” or “lodge by the cave”. This etymology reflects both its physical features—there are small caves nearby carved naturally into the rocky slopes—and its potential uses as a stopover point for travelers or members of the Inca elite.

Historical documents from Spanish chroniclers occasionally refer to similar "tampus" along key Inca roads. However, not all tampus were alike—many were administrative centers or storehouses; others served as places for ritual purification before entering Cusco. The association with “mach’ay” has encouraged speculation that Tambomachay was also linked with ancestral worship or rites involving subterranean spirits. Archaeological surveys have identified caves in the vicinity, some used for burials long before Inca times. Today’s guides sometimes reference both interpretations interchangeably; however, there is no definitive evidence about which meaning predominated for the Inca who used this particular site.

Historical Development: From Pre-Inca Use to Colonial Change

Although Tambomachay is widely recognized as an Inca construction from the 15th century, archaeological investigations suggest that its surroundings may have been significant even earlier. Lithic scatters and evidence of pre-Inca tombs suggest occupation during earlier periods by local groups such as the Killke culture (pre-120 CE). What differentiates Tambomachay is its finely carved masonry and the deliberate channeling of spring water—distinctive hallmarks of imperial Inca architecture under rulers like Pachacuti (ruled c. 1438–1471) or his successors.

Ethnohistorical sources—such as accounts by Guaman Poma de Ayala—mention royal hunting retreats in this region. Tambomachay’s location near game-rich grasslands makes it plausible that nobles stopped here before or after expeditions. During colonial times, Spanish authorities repurposed large tracts of land around Cusco into haciendas dedicated to cattle-raising or agriculture. A landowner named Mendoza managed Tambomachay’s area as private property well into the republican period; traces of enclosures and later structures still dot surrounding fields but do not directly affect the core hydraulic sanctuary.

It was only during systematic archaeological surveys in the 20th century—especially after Peruvian independence—that efforts were made to restore Tambomachay's original layout. Since then, access and conservation have gradually improved under oversight by Peru’s Ministry of Culture.

The Architecture: Platforms, Niches, and Precision Stonework

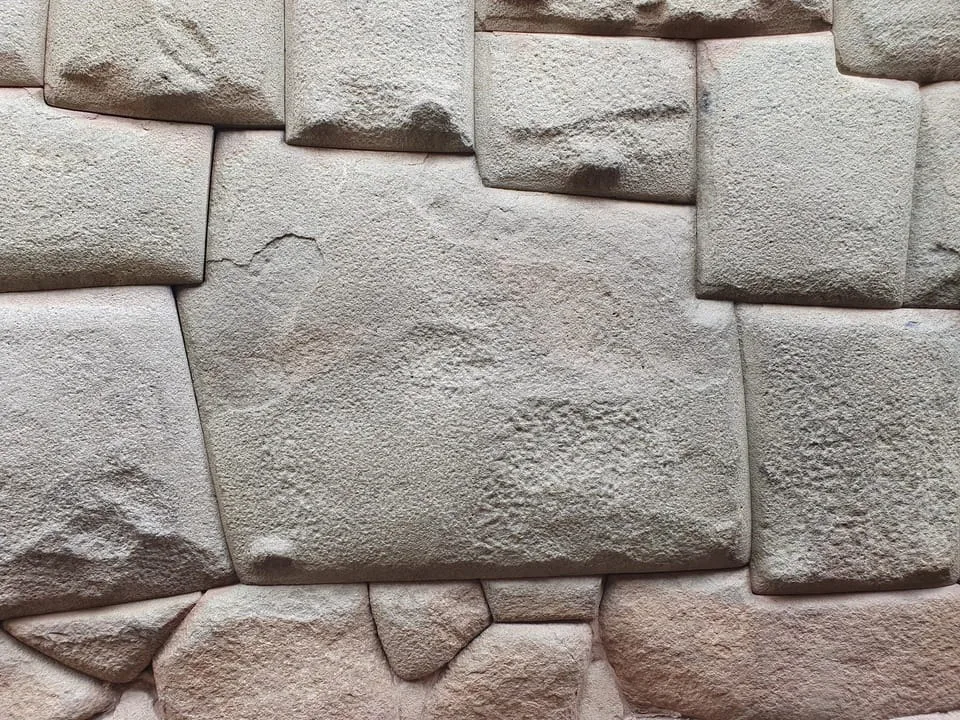

Visitors arriving at Tambomachay immediately notice its harmonious integration with the hillside: four main terraces rise up against a slope cut with geometric precision. The lowest two platforms consist of broad retaining walls built from polyhedral stones—each carefully shaped so that they fit together tightly without mortar, a hallmark of Inca design sometimes called sillar. These platforms support walkways where dignitaries likely stood during ceremonies.

Above these terraces sits a prominent wall punctuated by several large trapezoidal niches; some researchers believe these once held sacred objects or offerings (known as wak'a). On top of this highest platform are small stairs leading to an open space thought to serve either as an observation point or altar for ritual specialists (sometimes called amautas). Directly facing this central wall lie foundation remains interpreted as belonging to a circular structure—a type noted elsewhere in defensive lookout posts but also associated with ritual isolation.

Each element reflects a careful balance between functional necessity—the retention of soils prone to seasonal rains—and ceremonial visibility; ceremonies would be easily witnessed by those gathered below while remaining close to flowing water channels.

The Hydraulic System: Engineering Genius with Ritual Resonance

Perhaps the most remarkable feature at Tambomachay is its hydraulic infrastructure. Water emerges from natural springs higher up on the hill—a source whose flow remains steady throughout much of the year despite Andean climatic variation. The Inca artisans captured this spring using underground channels lined with finely joined stone slabs; these then guide water through conduits toward three main fountains set into the lower walls.

The best-preserved fountain splits its stream into two parallel jets that fall into separate basins below—a feat accomplished through angled channels hand-carved into individual blocks. Modern hydraulic engineers who have studied Tambomachay commend its efficiency: even moderate rainfall years see uninterrupted flow without overflow or clogging. It’s common during visits to see clear water pouring out decades—or centuries—after construction.

Interpretations about function vary among archaeologists: some propose these fountains purified initiates before festivals such as Inti Raymi; others emphasize their symbolism in maintaining harmony between human society and natural forces (Pachamama). Local oral tradition sometimes attributes healing or fertility properties to drinking from specific streams—a belief echoed in legends told by elders in adjacent communities.

Ceremonial Functions: Water Worship and Royal Rituals

The prominence given to water at Tambomachay points toward major ceremonial purposes beyond mere utility. For Andean societies—long before Inca consolidation—the relationship between water sources and sacred power was deeply embedded in cosmology. Inca priests performed offerings known as pagos a la tierra, seeking favor from mountain spirits (apus) to ensure rainfall for crops.

Chroniclers like Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa documented rituals where high-status individuals underwent ablutions at special fountains before participating in state events within Cusco itself; while these sources rarely name Tambomachay directly, its architecture closely matches such descriptions. Oral histories held among Quechua-speaking elders mention that only royalty or selected priests had access to particular pools on festival days (though mass participation likely occurred further downriver).

Comparisons can be drawn with other Andean shrines where springs emerge suddenly from rock faces—regarded as entrances to other worlds (ukhu pacha). Several contemporary researchers stress that Tambomachay should be read within this broader system rather than isolated: it was one node within networks linking landscape features believed to embody spiritual entities.

Tangible Features: What Visitors See Today at Tambomachay

Those visiting Tambomachay today encounter a compact yet aesthetically striking complex enclosed by modern stone boundaries that demarcate protected heritage zones. After passing through ticket booths operated by Peru’s Ministry of Culture—for international visitors this forms part of the Boleto Turístico del Cusco—the approach follows a gravel path flanked by eucalyptus trees introduced during recent decades but also remnant patches of native vegetation like qolle (Buddleja coriacea) and kantuta flowers (the national flower of Peru).

At peak times visitors line up along handrails overlooking the fountains themselves: clear water emerges from twin spouts set inside precisely carved alcoves, falling into rectangular basins whose overflow continues down terraced irrigation ditches toward lower fields now used for pasture rather than farming. Informational plaques summarize key facts in Spanish, English, and sometimes Quechua; on-site guides add context about how water was collected further uphill via small dams still visible if one follows less-trodden side paths.

Photography is allowed throughout most areas though touching walls or entering inner chambers is prohibited due both to conservation concerns and respect for ongoing ritual activities occasionally performed by indigenous groups on special dates tied to agricultural calendars.

The Route from Cusco: How Travelers Reach Tambomachay Today

Accessing Tambomachay is straightforward for most travelers staying in Cusco’s historic center. Taxis regularly depart from Avenida Sol; rides take 20–30 minutes depending on traffic and cost between 20–40 soles each way (as of 2024). Budget-conscious visitors sometimes take public buses heading toward Pisac but should note these drop passengers at junctions requiring short walks uphill.

Cyclists can rent mountain bikes from shops around Plaza San Blas; while gradients are moderate overall, thin air at altitude means even gentle slopes require acclimatization time—several agencies offer guided outings combining stops at nearby ruins such as Qenqo and Puca Pucara en route back down to Cusco.

A popular alternative involves organized tours led by licensed guides registered with DIRCETUR (Cusco’s regional tourism office). These half-day circuits typically start mid-morning and combine cultural explanations with practical advice about weather conditions—temperatures fluctuate rapidly in exposed highland locations even outside rainy season months (November through March). While some operators rush groups through multiple sites quickly, others emphasize slower exploration allowing time for reflection at each stop; always clarify itinerary details when booking since not all tours allocate equal time at Tambomachay itself.

Cultural Significance Today: Rituals, Community Engagement, Tourism Impacts

Despite its status as a protected archaeological monument under Peruvian law since 1983,Tambo-machay remains more than just a tourist attraction—it continues serving symbolic functions in modern Andean community life. Certain dates on traditional agricultural calendars see local families gathering discreetly near springs for private offerings involving corn beer (chicha de jora) and flower petals; while technically discouraged within strict preservation areas, these acts persist under tacit understanding between custodians and local populations who view them as essential continuities rather than disruptions.

Tourism brings both benefits—increased income opportunities for guides, drivers, artisans selling textiles near entrances—and challenges such as pressure on fragile surfaces or crowding during high seasons (notably June when festivities mark Inti Raymi nearby). Conservation projects over recent years have focused not just on stabilizing ancient walls but improving drainage systems vulnerable to erosion caused by heavy visitor traffic or unseasonal storms intensified by climate change trends observed across southern Peru.

Outreach programs led by local universities sometimes bring school children from rural districts to experience their heritage firsthand; feedback suggests pride but also concern that so much visitation risks trivializing what many view first as sacred territory rather than museum exhibit.

Tangible Legends and Local Lore Associated with Tambomachay

Several oral traditions circulate among residents living within sight of Tambomachay. One enduring story recounts how Pachacuti—in some versions his successor Tupac Yupanqui—would rest here after successful hunting trips accompanied only by loyal retainers; elders say he sought strength from “living waters” believed capable of purifying mind as well as body.

Another legend attributes romantic powers to pools fed by main springs: young couples sometimes visit discreetly hoping joint hand-washing will guarantee fidelity or fertility—a motif mirrored at distant Andean sites but especially persistent around Cusco valleys.

There are also tales involving spectral guardians said to appear on misty mornings guarding “hidden gold,” a narrative probably amplified after Spanish conquest when rumors spread about lost treasures buried in mountain caves.

Most stories blend pragmatic environmental awareness (“do not waste spring water”) with reverence for forces invisible yet always present beneath surface realities—a perspective shared by many contemporary Andean spiritual practitioners who trace their rituals back through generations rooted in these very hillsides.

The Role of Archaeological Research: Methods and Discoveries

Professional excavations at Tambo-machay have been comparatively limited compared with sites like Machu Picchu or Sacsayhuaman but nonetheless yielded valuable insights since early 20th-century mapping campaigns initiated by Peruvian archaeologists Luis E. Valcárcel and Julio C. Tello.

Early investigations focused on documenting masonry techniques unique to eastern outskirts of imperial Cusco; subsequent work mapped underground channels confirming advanced hydrological understanding absent mechanical pumps.

Recent research employs non-invasive methods such as ground-penetrating radar (GPR) revealing buried architectural elements possibly related to pre-Inca ceremonial grounds overshadowed by later construction.

Ongoing collaborations between Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú specialists and international partners study microflora surviving within irrigation ditches—a project aiming both at ecological conservation and better understanding how ancient approaches sustained clean flow despite sedimentation risks.

Results published in peer-reviewed journals like “Latin American Antiquity” enhance appreciation for technical sophistication achieved long before European contact disrupted indigenous systems.

Despite gaps remaining about precise timing or patronage behind specific features—documentary evidence remains fragmentary—it is widely agreed now that Tambo-machay exemplifies late imperial craftsmanship rather than being simply another roadside tambo serving common travelers.

For latest updates readers may consult official Ministry reports (Peruvian Ministry of Culture website – Cultura Perú).

Sustainable Tourism Practices at Tambomachay

With visitor numbers rising steadily since early 200s,Tambo-machay faces mounting pressures necessitating thoughtful management choices balancing preservation with educational access.

Ministry staff regularly rotate cleaning schedules removing debris left behind after peak holidays;

interpretive signage now asks guests not only refrain touching stones but avoid littering especially near streambeds since plastic waste can clog delicate flows critical both archaeologically and ecologically.

Collaborative programs—involving regional tourism boards plus community leaders based in Ccorao/Ccorcca—experiment with rotating vendor stalls so economic benefits spread more evenly rather than clustering around single concessionaires.

Feedback solicited annually helps identify bottlenecks where crowding impacts experience negatively—for instance suggestions implemented 2023 included staggered ticket entry times at end-of-year school group peaks.

Efforts continue raising awareness among domestic tourists about why short visits matter less than meaningful engagement respecting living heritage values many local families still cherish.

For travelers seeking deeper involvement specialized workshops arranged seasonally introduce basics behind Andean cosmology/festivals contextualizing Tambo-machays role beyond sightseeing alone.

For more information regarding official opening hours/fees see trusted resource:

Peru Travel – Official Tourist Information.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is swimming or bathing allowed in Tambomachay's fountains?

No bathing or swimming is permitted in any area of Tambomachay's fountains or pools. These structures are protected archaeological features considered sacred by local communities and closely monitored by park authorities. Entering waterways causes erosion risk and disrupts delicate hydraulic systems dating back centuries. - Do I need an advance ticket reservation for Tambomachay?

A standard entrance ticket for Tambomachay forms part of the multi-site "Boleto Turístico del Cusco", available online or at authorized offices throughout Cusco city center. While reservations are not strictly required outside major holidays, purchasing tickets ahead ensures smoother entry especially during peak visitor periods like June festival season. - What language(s) are informational plaques presented in onsite?

Most onsite signs provide information primarily in Spanish; English translations are common particularly near main fountain areas. Occasional Quechua-language panels highlight local terminology relevant for those interested in authentic Andean perspectives. - Are there accessibility accommodations for visitors with reduced mobility?

Paths leading from parking lot up toward fountain terraces are mostly gravel surfaced with moderate inclines; while assistance rails exist along principal routes those requiring wheelchair access may encounter difficulty especially during rainy months due uneven terrain conditions typical across highland archaeological parks. - Does Tambomachay host any annual festivals open to tourists?

While no major public festival takes place solely at Tambomachay itself today due preservation policies certain community-led rituals occur nearby aligned agricultural calendar; Inti Raymi celebrations based mainly Sacsayhuaman occasionally include traditional processions passing close-by but main performances remain centered within Cusco city proper.