Perched over 3,500 meters above sea level in the heart of the Sacred Valley, Moray stands as one of Peru’s most intriguing archaeological complexes. Its concentric terraces, spiraling down into natural depressions, have sparked debates and research since their rediscovery in the early twentieth century. While at first glance they appear to be simple amphitheaters, a closer look reveals a sophisticated agricultural laboratory that sheds light on Inca ingenuity and their deep understanding of environmental management.

Geographical Setting and Access to Moray

Moray is located about 50 kilometers northwest of Cusco, near the colonial village of Maras. The site is positioned on a high plateau above the Urubamba Valley, where the landscape is defined by undulating hills, dramatic mountain backdrops such as the snow-capped peaks of Chicon and Veronica, and expansive fields cultivated by local communities. Travel to Moray today typically begins in Cusco, with routes passing through Chinchero and Maras before winding towards the archaeological complex. Most visitors arrive via organized tours, but independent travelers can reach Moray by taxi or hiking routes that connect nearby attractions, including the famous Maras salt pans.

The climate around Moray is semi-arid with marked seasonal variation—rainfall concentrates between November and March, while dry months from May to September offer clearer skies and better walking conditions. Temperatures fluctuate substantially throughout the day due to altitude, often requiring layers for comfort. This climatic diversity is not coincidental; it mirrors the microclimates that make Moray’s terraces unique among Andean sites.

The Structure and Architecture of Moray’s Terraces

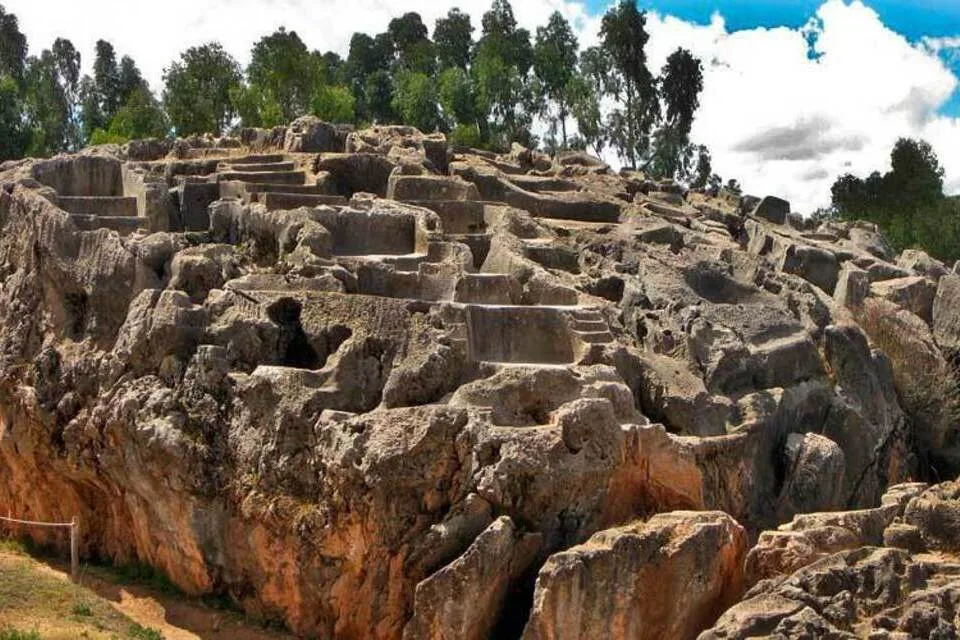

The most striking feature of Moray is its system of circular terraced depressions, each resembling a giant amphitheater carved into natural sinkholes known locally as “muyus”. The largest depression reaches approximately 30 meters in depth and consists of twelve circular levels descending concentrically. The diameter of the outermost circle exceeds 180 meters, making it one of the most expansive terraced constructions attributed to the Incas.

Each terrace is supported by finely fitted stone retaining walls and filled with soil transported from different regions of the Andes—a detail confirmed through soil analysis conducted by Peruvian archaeologists since the late twentieth century. Staircases made from flat stones inserted into terrace walls enabled movement between levels for those working or experimenting within these structures. Drainage was carefully managed with underlying layers of gravel, preventing erosion during rainy seasons. The entire layout demonstrates an advanced grasp of engineering principles adapted to a challenging environment.

Purpose: Moray as an Agricultural Research Center

The prevailing scholarly consensus positions Moray as an agricultural testing ground rather than a ceremonial or purely aesthetic site. Early investigations by archaeologists such as Julio C. Tello in the 193s suggested that each terrace created its own microclimate: temperature differences between top and bottom levels could reach up to 15°C (59°F). These controlled conditions allowed Inca agronomists to simulate growing environments found at various altitudes across their vast empire.

The Incas cultivated staple crops such as maize (corn), potatoes, quinoa, oca, and amaranth in Moray’s terraces. By adjusting variables like temperature exposure, soil composition, humidity, and irrigation methods, they selectively bred plants for resilience and productivity under varying Andean conditions. Evidence indicates that experimentation here contributed directly to crop diversification—key to food security across regions ranging from tropical lowlands to high-altitude settlements.

This interpretation is supported by botanical analysis performed on remnants discovered during excavations. However, while some hypotheses about ceremonial uses persist (notably due to certain alignments with celestial events), there remains little direct evidence for regular ritual activity compared to sites like Sacsayhuamán or Qorikancha.

Cultural Significance in Inca Society

Moray reflects both technological mastery and reverence for nature integral to Andean culture. In Inca cosmology, agriculture was interwoven with religious duty; Pachamama (Mother Earth) was venerated through offerings at planting and harvest times. Sites like Moray exemplify this relationship—here, technological innovation went hand-in-hand with respect for ecological balance.

The diversity managed within Moray’s terraces echoes broader practices observed throughout Tawantinsuyu (the Inca state), where communities adapted cultivation strategies according to local topographies and microclimates. Oral traditions from nearby villages reference ancestral knowledge passed down through generations regarding plant selection and land stewardship; some current farmers near Maras still select potato varieties using principles akin to those inferred from Moray’s design.

Cultural events occasionally take place at or near Moray today—notably during Inti Raymi (the Festival of the Sun) or regional fiestas honoring agricultural cycles. These contemporary practices do not directly replicate Inca ceremonies but underscore ongoing connections between landscape management and spiritual observance among Andean peoples.

Scientific Investigations: From Early Explorers to Modern Research

The first systematic studies at Moray began in earnest during the 193s with Peruvian archaeologists like Tello, followed by international teams throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Core sampling revealed that soils within each terrace layer were often imported from different ecological zones—a finding suggesting intentional experimentation rather than random construction.

Microclimate measurements conducted over several decades have confirmed significant differences in temperature, humidity, and sunlight exposure among terrace levels. These observations support theories about crop adaptation trials conducted here by Inca specialists known as “mitmaqkuna”, who were relocated experts overseeing experimental agriculture across imperial territories. Ongoing studies led by institutions such as Cusco’s National Institute of Culture continue to probe water management techniques employed at Moray and their applicability for sustainable farming today.

The site has also become a reference point for modern discussions about agrobiodiversity conservation—organizations like Bioversity International have highlighted Moray when advocating for native crop protection amid climate change pressures affecting Andean agriculture.

The Daily Life Around Moray: Then and Now

While there are no surviving chronicles detailing everyday activity specifically inside Moray, comparative studies with other Inca centers provide plausible insights. Specialists likely lived nearby or commuted from adjacent settlements such as Maras or Chinchero; they may have worked under supervision from higher-ranking administrators based in Cusco or Ollantaytambo.

The labor required for constructing terraces—and maintaining them seasonally—entailed cooperation between skilled stonemasons, agriculturalists familiar with highland crops, and water engineers adept at channeling scarce rainfall without risking landslides. Oral accounts suggest that families from neighboring ayllus (kinship groups) periodically assisted with major tasks such as wall repairs or planting cycles—a model echoed elsewhere in pre-Hispanic Andean society.

Today, farmers living along routes connecting Maras to Moray continue cultivating varieties that may descend from experiments conducted centuries ago. During certain times of year (particularly harvest), visitors see local women sorting native potatoes or young men tending barley fields on surrounding slopes—offering continuity between past innovation and present subsistence practices.

Visiting Moray: Practical Information for Travelers

Moray is open year-round under supervision by Peru’s Ministry of Culture; entrance fees apply as part of the “Boleto Turístico del Cusco”, which grants access to multiple archaeological sites within the region (official ticket information here). Most visitors arrive mid-morning after stopping at Chinchero or Maras salt mines; early afternoons tend to be quieter except during peak tourist season (June–August).

- Best time to visit: Dry months (May–September) provide clearer views and more stable walking conditions.

- Getting there:

- By tour: Most agencies in Cusco include Moray alongside Maras salt ponds and Chinchero market on day trips.

- By public transport: Buses go as far as Maras village; onward travel usually requires a taxi or organized hike (about 8 km/5 miles).

- Cycling: Adventure companies offer bike tours connecting several Sacred Valley highlights—including challenging descents towards Urubamba.

- Amenities: There are basic restrooms at site entrance but limited food options; travelers should bring water and snacks.

- Sustainable tips: Respect existing trails—cutting across terraces damages ancient infrastructure—and avoid removing rocks or plants from archaeological zones.

The Role of Moray in Contemporary Peruvian Identity

Moray, beyond its archaeological allure, serves as a symbol of resilience in Peruvian heritage discourse. For many locals—especially those engaged in indigenous rights movements—it represents ancestral wisdom related to land use innovation rather than simply a tourist attraction. Educational programs frequently incorporate site visits or workshops informed by studies at Moray; these aim both to transmit traditional agricultural techniques and foster pride among younger generations whose livelihoods remain tied to highland farming systems.

Museums such as Cusco’s Museo Inka feature exhibits referencing research carried out at Moray alongside displays dedicated to ancient tools recovered nearby (Museo Inka official site). Local festivals often include dramatizations depicting pre-Hispanic agricultural life—a practice seen annually during provincial celebrations around June 24th, when communities parade using costumes inspired by regional history.

This evolving cultural resonance situates Moray within wider debates concerning sustainable development in Andean regions facing pressures from migration, tourism growth, climate variation, and shifting economic priorities. It acts both as a reminder of what careful stewardship once achieved—and what might again be possible using lessons drawn from Inca-era experimentation with diversity and adaptability.

The Impact of Tourism on Conservation Efforts at Moray

The rise in visitor numbers over recent decades has brought new opportunities—and risks—to Moray. Revenue collected through entry fees funds ongoing excavation work and structural maintenance coordinated by Peruvian heritage authorities. Nevertheless, increased foot traffic poses real challenges: gradual erosion along paths leading between terraces has prompted reinforcement projects using traditional techniques wherever feasible.

Sustainable tourism guidelines encourage tour operators to limit group sizes within core areas; some agencies collaborate with local guides who share personal insights about farming traditions linked historically with Moray’s function. Conservationists emphasize balancing economic benefits generated through tourism against longer-term preservation imperatives—a delicate negotiation occurring at many prominent Inca sites including Machu Picchu and Ollantaytambo.

A few pilot projects seek ways to integrate community-based tourism more directly into regional development—such as training programs for young guides fluent in Quechua or workshops teaching heritage craft skills inspired by archaeological finds from sites like Moray (UNESCO - Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu context). While not all such efforts succeed uniformly due to logistical constraints or shifting visitor interests, they represent ongoing attempts to reconcile access with stewardship goals rooted in local participation rather than external direction alone.

Biodiversity Connections: Lessons for Modern Agriculture

The scientific legacy of Moray continues influencing dialogues about biodiversity conservation well beyond Peru’s borders. Agronomists studying climate-resilient crops reference historical adaptation strategies practiced here—especially relevant given present-day concerns about global food security under shifting weather patterns. Universities occasionally partner with Andean research centers near Cusco for comparative field trials drawing inspiration from ancient multi-level terrace designs used at Moray; results sometimes inform seed banking initiatives aimed at preserving rare potato varieties unique to Peruvian highlands (International Potato Center - CIP Lima).

Certain NGOs facilitate exchanges between farmers from regions experiencing comparable environmental stresses—sharing experiences gleaned through work undertaken within traditional frameworks like those seen at Moray’s concentric terraces.

These collaborations illustrate how ancient knowledge can inform contemporary sustainability debates without romanticizing pre-modern societies or suggesting direct transferability out of context; instead they invite careful consideration regarding adaptation mechanisms rooted in observation over centuries rather than decades alone.

Frequently Asked Questions

- Why did the Incas build circular terraces at Moray instead of rectangular ones?

The circular design allowed more precise control over environmental factors like temperature and humidity across varying levels. Each ring offered slightly different conditions due to changing sunlight angles and wind patterns throughout the day—enabling nuanced experimentation not easily achieved with conventional rectangular terraces common elsewhere in Peru. - Can you visit both Moray and Maras salt pans on one trip?

Yes—it is common for travelers based in Cusco or Urubamba to combine visits as both sites are located within 10 kilometers of each other near Maras village. Most tour agencies offer half-day excursions covering both locations; independent travelers can hire local taxis between sites or hike if prepared for uneven terrain. - Are there any original Inca artifacts displayed at Moray?

There are no permanent museum facilities onsite displaying original artifacts found during excavations. Some ceramics or tools unearthed near Moray appear occasionally in rotating exhibits at museums in Cusco such as Museo Inka or Museo Regional. Onsite interpretation focuses primarily on architectural features rather than movable relics. - Is photography allowed inside the archaeological complex?

Photography for personal use is permitted throughout Moray, though use of tripods may require special permission from authorities. Commercial shoots need advance permits obtained via Peru's Ministry of Culture. Visitors are encouraged not to enter restricted areas or climb retaining walls while taking photos. - How long does it take to explore all parts of Moray?

Most visitors spend one-and-a-half to two hours walking around all three main depressions plus secondary viewing points scattered along marked trails. Those combining their visit with hikes towards Maras village—or participating in guided tours focusing on agricultural history—may wish to allow additional time accordingly. Facilities are minimal so plan ahead regarding water breaks.